Vor 70 Jahren bebte Helgoland: 6700 Tonnen Sprengstoff gezündet

Britain's 'big bang' in Heligoland, 70 years on - BBC News

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39590752?SThisFB

Vor 70 Jahren bebte Helgoland: 6700 Tonnen Sprengstoff gezündet

Es war die weltweit größte nicht-atomare Sprengung: Vor 70 Jahren wollten die Briten die militärstrategisch exponierte Insel Helgoland „auf Dauer wehruntüchtig“ machen.

Britain's 'big bang' in Helgoland, 70 years on

Brexit may have triggered a political earthquake in Europe, but 70 years ago the UK sent real shockwaves across the seas with the largest non-nuclear explosion of that era.

As one of the four victorious allied powers after World War Two, Britain was governing a large area of occupied Germany.

The British sector included the tiny island of Heligoland, which had long been a source of diplomatic tension between the two countries.

So, when in 1947 the British needed a safe place to dispose of thousands of tonnes of unexploded ammunition, Heligoland must have seemed an obvious choice.

The code-name for the plan combined the British flair for understatement with the military taste for the literal-minded; it was to be called Operation Big Bang.

Vor 70 Jahren bebte Helgoland: 6700 Tonnen Sprengstoff gezündet

Es war die weltweit größte nicht-atomare Sprengung: Vor 70 Jahren wollten die Briten die militärstrategisch exponierte Insel Helgoland „auf Dauer wehruntüchtig“ machen.

The code-name for the plan combined the British flair for understatement with the military taste for the literal-minded; it was to be called Operation Big Bang.

PATHE

PATHEHeligoland had been a German naval fortress, and historian Jan Rueger, author of Britain, Germany, and the Struggle for the North Sea, says Operation Big Bang was designed by the British to make a big point.

"They're very clear that there's a symbolic side to this [operation] and that is the German tradition of militarism," he explains.

"There's a sense that Prussian militarism and its threat to Britain has to end and that's very much how Operation Big Bang is received in Britain."

The operation was carefully stage-managed - the old black and white pictures even include a close-up of a Royal Navy officer's finger triggering the blast. Aerial footage shows the entire horizon erupting in a huge grey curtain of mud, sand and rock.

For the Royal Navy and the British Army of Occupation it was mission accomplished.

PA

PAVor 70 Jahren bebte Helgoland: 6700 Tonnen Sprengstoff gezündet

Es war die weltweit größte nicht-atomare Sprengung: Vor 70 Jahren wollten die Briten die militärstrategisch exponierte Insel Helgoland „auf Dauer wehruntüchtig“ machen.

For the people of Heligoland it felt very different.

Europe in 1946 and 1947 was in chaos, with millions of displaced and dispossessed families drifting between camps or sheltering in ruined buildings.

The island had been evacuated during the war and many Heligolanders were living in exile in the coastal city of Cuxhaven about 60km (37 miles) to the south.

Olaf Ohlsen, who was 11 years old in 1947, gathered with the rest of the exiled population on the cliffs to listen for the sound of the explosion.

Few people in history can have lived through such a moment, standing at the edge of sea knowing that they would hear but not see an explosion that they knew would destroy their homes.

Olaf says everyone knew that the explosion would be shattering.

"Even in Hamburg, which is more than 150 km (93 miles) from the island," he told me, "a schoolteacher kept a document which said the British had warned everyone to leave doors and windows open to help the buildings withstand the blast."

Olaf's father was among the pessimists who believed that Britain's real intention was to blow up the island behind a literal smokescreen created by the destruction of the captured ammunition.

He still recalls the first time his father brought news of what had happened after the blast, shouting with excitement: "Heligoland is still here, it's still here."

In the middle of the 20th Century Heligoland still mattered to its people, fiercely independent speakers of a Friesian dialect who are neither British nor German.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESBut it had lost the strategic importance that made it a crucial bone of contention between the great powers of Europe a hundred years earlier.

Britain occupied Heligoland in the Napoleonic period as part of its complex manoeuvrings to deny the French leader the support of the navies of Scandinavia as he took over huge parts of Europe.

Thus the British found themselves with a handy naval base that guarded the entrance to the port of Hamburg and allowed it to slip secret agents freely into Napoleonic Europe. By the time they gifted it to the Kaiser in 1890, though, its usefulness appeared to be at an end.

Detlev Rickmers, a local hotel owner whose family have been Heligolanders for 500 years, says that even though it's more than a century since the link was broken, a sense of Britishness ran through the population for a long time after 1890.

"Of course there was a British governor, there was a sense of being British," he says. "There were connections to Britain. My grandfather told me that he always remembered the excitement of the days when the salesman would call from Huntley and Palmer."

In the wake of the Big Bang, of course, things are very different.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESThe British bombing operation acted as a kind of catalyst for a new form of post-war German nationalism.

There were campaigns for the island to be returned to German sovereignty and for a rebuilding programme to allow the Heligolanders to go home.

Historian Jan Rueger says that perhaps for the last time Operation Big Bang had made Heligoland part of a larger historical argument.

"As always in history there's a paradoxical side to these events," he says. "In this case it lies in the way that all over Germany this is seen as a moment that victimises the Germans and allows them to see themselves as victims after a war in which the rest of Europe has been the victim of German aggression."

The British bombing left Heligoland's landscape pock-marked and cratered. But the island endured: a stubborn lump of rock in the North Sea.

And while most visitors are drawn these days by the lure of duty-free shopping, Heligoland has a fascinating story to tell to anyone who'll listen.

Vor 70 Jahren bebte Helgoland: 6700 Tonnen Sprengstoff gezündet

Es war die weltweit größte nicht-atomare Sprengung: Vor 70 Jahren wollten die Briten die militärstrategisch exponierte Insel Helgoland „auf Dauer wehruntüchtig“ machen.

HELGOLAND | Der Rauchpilz über Helgoland stieg damals fast 1500 Meter hoch in den Himmel, Teile des markanten roten Sandsteins stürzten in die Nordsee. Die Felseninsel „überlebte“ jedoch die gigantische Sprengung vor 70 Jahren, denn der relativ weiche Buntsandstein der Insel absorbierte einen Großteil der Sprengwirkung. „Selbst im mehr als 100 Kilometer entfernten Hamburg gab es noch Warnungen wegen der britischen Militäroperation Big Bang“, sagte am Dienstag Helgolands Tourismusdirektor Klaus Furthmeier.

Helgoland liegt militärstrategisch günstig in der Deutschen Bucht. Im Zweiten Weltkrieg sollte die kleine Insel als deutsche Militärbasis massiv ausgebaut werden, was aber nicht in dem Maße erfolgte.

6700 Tonnen Munition und Sprengstoff detonierten und schlugen bis heute unheilbare Wunden in die Topographie von Deutschlands einziger Hochseeinsel.

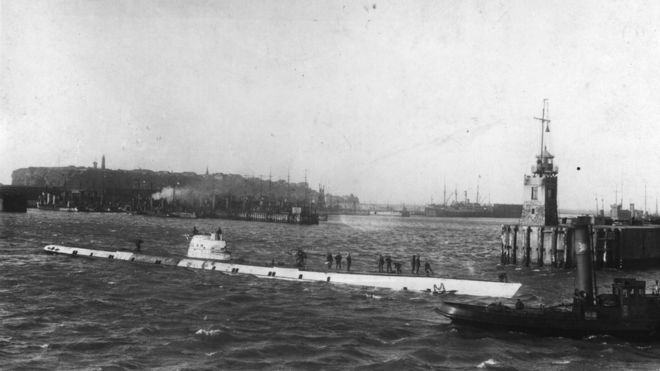

Es ging um die Zerstörung der 1945 weitgehend unbeschädigt gebliebenen U-Boot-Bunker sowie der weit verzweigten 15 Kilometer langen Festungsanlagen.

Die Dimension der in der Weltgeschichte bislang größten nicht atomaren Sprengungsaktion ist nur schwer vorstellbar.

Die US-Streitkräfte warfen Anfang April ihre größte Bombe GBU-43 („Mother of all Bombs“) über Afghanistan ab - sie hat mehr als 8000 Kilogramm Sprengstoff und elf Tonnen TNT-Äquivalent.

Rein rechnerisch hätte es 609 solcher moderner Monster-Bomben gebraucht, um die Zerstörungskraft wie am 18. April 1947 auf Helgoland zu erreichen.

Für die „Operation Big Bang“ stapelten die Briten viertausend Torpedosprengköpfe, neuntausend Wasserbomben und neunzigtausend Granaten in das vom deutschen Militär geschaffene Tunnellabyrinth Helgolands.

Per Fernzünder von einem Schiff aus neun Kilometer Entfernung lösten die Briten die Sprengung aus. Dabei wurden nicht nur die militärischen Anlagen vernichtet, sondern im Süden ein Teil der Steilküste aus Buntsandstein mitgerissen.

Geröllmassen bedeckten einen Teil des Unterlandes: Das oberhalb des Hafens liegende Mittelland war entstanden. „Die immer noch verbreitete Ansicht, die Briten hätten Helgoland komplett zerstören und in der Nordsee verschwinden lassen wollen, ist definitiv falsch“, sagte Fuhrtmeier. „Ich habe mir den militärischen Befehl extra nochmal durchgelesen, da steht ausdrücklich drin, die Insel ,auf Dauer wehruntauglich' zu machen.“

Zum Zeitpunkt der Sprengung war Helgoland schon seit zwei Jahren nicht mehr bewohnt.

Kurz vor Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges, ebenfalls am 18. April (1945), legten fast 1000 britische Bomber sämtliche Gebäude in Schutt und Asche.

In Bunkeranlagen konnten die 2500 Bewohner überleben, das Eiland wurde aber Tage später geräumt.

Jahrelang nutzte die britische Luftwaffe nach Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs das Felsen-Eiland als Übungsplatz für ihre Bomber.

Erst 1952 durften die über ganz Norddeutschland verstreuten Helgoländer auf ihre Insel zurück.

Heute leben knapp 1500 Menschen dort.

„Die Helgoländer haben ein viel intensiveres, tiefer gehendes Heimatgefühl als andere“, sagte Furthmeier.

„Die Ungewissheit, ob sie überhaupt und wann sie zurückkehren könnten, haben die Gefühlswelt der Menschen geprägt.“

Hinzu kämen die sichtbaren Veränderungen der Insel durch Bomben und Sprengungen - „etwa Bombenkrater, die manche Touristen heute nutzen, um windgeschützt ein Glas Wein zu genießen.“

Jeweils am 18. April gedenken die Helgoländer der „Operation Big Bang“ und der Bombenangriffe.

„Das sonnige Wetter am Dienstag ließ umso traumatischer das Leid und Elend von damals bewusst werden“, sagte Pastorin Pamela Hansen.

Protestanten und Katholiken feierten in St. Nicolai einen ökumenischen Gottesdienst, bei dem die Helgoländer Glocke - sie war zur Wieder-Besiedelung Helgolands 1952 gestiftet worden - und die Totenglocke zur Erinnerung an die Opfer der beiden Weltkriege erklangen.

An einer Gedenktafel wurde ein Kranz niedergelegt.

Als Urlaubsziel wird Helgoland mit seinen weißen Sandstränden immer beliebter.

„Das gilt vor allem für Urlauber, die auch über Nacht bleiben“, sagte Furthmeier. 2016 kamen 359.000 Tagesgäste und Urlauber - rund 19 Prozent mehr als 2015.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen